Donor Family Support Resources

The Transplant Support Group (Malta) thank the generous donors and their families who save and transform the lives of others through the gift of organ and tissue donation. We would like to help you and your family with some support material that may help you in your difficult journey.

The Transplant Support Group (Malta) would like to thank:

Australian Government | Organ and Tissue Authority for permission to utilise resources on their website.

If you are reading this information, it may be because someone you love has died, or it is expected that they will die soon. You may have been asked to consider organ and tissue donation. This is an important and rare opportunity that can help others in need of a transplant.

Some families have discussed organ and tissue donation and may already know their loved one’s wishes. Other families who have not discussed donation may also need to make a decision about whether their loved one will become a donor. This page provides information to support you and your family to make a decision about donation that is right for your loved one and for you.

It is important to know that donation will only happen if consent is given by a patient or their senior next of kin.

Understanding Death & Donation

Organ and tissue donation involves removing organs and tissues from someone who has died (a donor) and transplanting them into someone who, in many cases, is very ill or dying (a recipient).

Organ donation and transplantation

Organ donation can be performed only from patients that are brain dead.

The organs that can be transplanted include the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, intestine and pancreas. In Malta, only the heart and the kidneys are transplanted. Maltese patients requiring liver and lung transplantation would need to have the required surgery performed abroad.

Tissue donation and transplantation

Tissue donation can be performed from cadavers that die either of Brain death or Circulatory death.

Tissues that can be transplanted include heart valves and other heart tissue, bone, tendons, ligaments, skin and parts of the eye such as the cornea. In Malta the tissues transplanted are the corneas.

Death must have occurred before donation can take place.

Death can be determined in two ways:

- Brain death occurs when a person’s brain permanently stops functioning.

- Circulatory death occurs when the circulation of blood in a person permanently stops.

It is important to understand the difference between brain death and circulatory death. The way a person dies influences how the donation process occurs and which organs and tissues can be donated.

Brain death occurs when the brain has been so badly damaged that it completely and permanently stops functioning. This can occur as the result of severe head injury (for example after a fall or motor vehicle accident), a stroke from bleeding (haemorrhage) or blockage of blood flow in the brain, brain infection or tumour, or following a period of prolonged lack of oxygen to the brain.

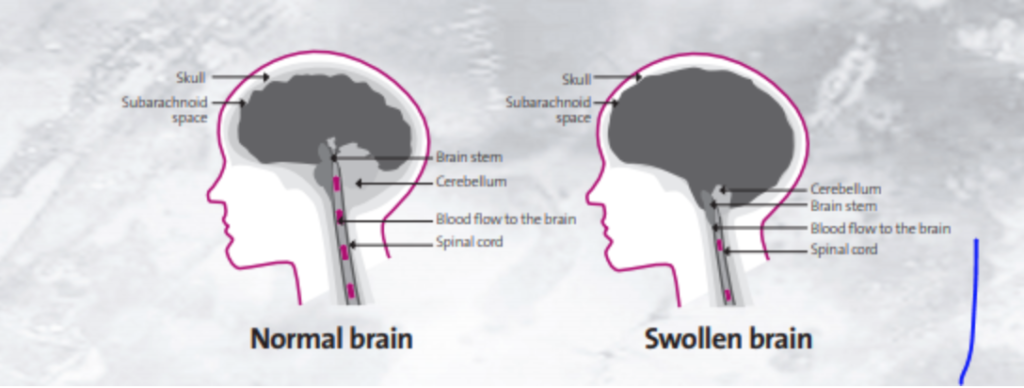

Just like any other part of the body, when the brain is injured it swells. The brain is contained within a rigid ‘box’, the skull, which normally protects it from harm but also limits how much the brain can expand. This is different to other parts of the body, such as an injured ankle, that can continue to swell without restriction. If the brain continues to swell, pressure builds up within the skull causing permanently damaging effects.

The swelling places pressure on the brainstem where the brain joins with the spinal cord at the back of the neck. The brainstem controls many functions that are necessary for life including breathing, heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature.

As the brain swelling increases, the pressure inside the skull increases to the point that blood is unable to flow to the brain (see Diagram 1). Without blood and oxygen, brain cells die. Unlike many other cells in the body, brain cells cannot regrow or recover. If the brain dies, that person’s brain will never ever function again, and the person has died. This is called “brain death”.

Diagram 1

The brain and brainstem control many of the body’s vital functions, including breathing. When a person has suffered a brain injury, they are connected to a machine called a ventilator, which artificially blows oxygen into the lungs (ventilation). The oxygen is then pumped around the body by the heart. The heartbeat does not rely on the brain, but is controlled by a natural pacemaker in the heart that functions when it is receiving oxygen.

While a ventilator is providing oxygen to the body, the person’s chest will continue to rise and fall giving them the appearance of breathing, their heart will continue to beat and they will feel warm to touch. This can make it difficult to accept that death has occurred. However, even with continued artificial ventilation, the heart will eventually deteriorate and stop functioning.

How do doctors know that a person’s brain has died?

People who are critically ill in hospital are under constant observation by the specialist medical and nursing teams caring for them and are closely monitored for changes in their condition. There are a number of physical changes that take place when the brain dies. These include loss of the normal constriction of the pupils to light, ability to cough, inability to breathe without the ventilator, and reduced blood pressure and body temperature.

When the medical team observes these changes they will perform clinical brain death testing to confirm whether the brain has stopped functioning or not.

Two senior doctors will independently conduct the same set of clinical tests at the bedside. The doctors performing the brain death testing will be looking to see if the person has any:

- response to a painful stimulus

- pupil constriction when a bright light is shone in the eye

- blinking response when the eye is touched

- eye movement when ice cold water is put into the ear canal

- gag reaction when the back of the throat is touched

- cough when a suction tube is put down the breathing tube

- ability to breathe when the ventilator is temporarily disconnected.

The above movements/reactions are the responses of nerves coming from the brain and therefore if a person shows no response to all of these tests, it means that their brain has stopped functioning and the person has died. Although the heart will still be beating because oxygen is still getting to the heart with the assistance of the ventilator. the person is declared dead and a death certificate is issued – from then on, the person declared dead is a cadaver.

There are times when the person’s injury or illness means that clinical brain death testing cannot be done. For example, facial injuries may limit examination of the eyes or ears. In these circumstances medical imaging tests are done to determine if there is any blood flow to the brain (a cerebral angiogram or cerebral perfusion scan). The hospital staff will provide further information if such a test is necessary.

What happens after brain death has been confirmed?

Once brain death has been confirmed, the cadaver will remain connected to the ventilator while members of the healthcare team speak with the person’s family about the next steps. These will include the person’s end-of-life wishes, the opportunity for organ and tissue donation and timing of removing the ventilator.

N.B. Kindly note the use of the word ‘cadaver’ once the person is declared brain dead. This is to avoid confusion as relatives often find it hard to accept that their loved one who still seems to be breathing (via the ventilator) is dead.

If the individual has already shown his or her support for organ donation by signing up as an official donor throughout his or her life, or if the family supports organ donation, everything possible will be done to make sure those wishes are fulfilled. Timeframes can vary as every circumstance is different. It can take an extended period of time for the necessary arrangements for donation to be made. The cadaver will remain connected to the ventilator and medications provided to support the blood pressure and keep oxygen circulating to the organs. Increased medical activity may be seen around the cadaver, due to further tests such as chest X-rays. If it becomes clear that organs are not suitable for donation, the senior next of kin will be notified and it may still be possible for the donation of tissue including eye, heart, bone and skin to occur.

When the arrangements for donation have been made, the cadaver will be moved to the operating theatre for the organ and tissue retrieval surgery. The ventilator will be removed during the operation.

If donation is not supported, the doctor will speak with the family about removing the ventilator. When the ventilator is removed, the cadaver’s heart will stop beating due to a lack of oxygen and their skin will become cold and pale because blood is no longer being circulated around the body.

Care, dignity and respect are always maintained during end of life care, whether or not donation proceeds.

Circulatory death occurs when a person stops breathing and their heart stops beating (there is no blood flow in the body). This can occur after a sudden illness or accident, or can be the final stage of a long illness.

Organ donation is sometimes possible after circulatory death although only in particular situations, as organs quickly deteriorate once blood flow to them stops. The usual circumstance is when a person is in an intensive care unit following a severe illness from which they cannot recover and the doctors and family agree it is in the person’s best interests to remove artificial ventilation and any other life supports. This may occur following a very severe brain injury resulting in permanent severe disability, people with terminal heart or lung failure, or people who have suffered a very severe spinal injury where they cannot move or breathe unassisted.

NB – Organ donation after circulatory death is not practised in Malta due to ethical issues.

When donation is able to occur, the person who has died will be moved to an operating theatre for surgery. Below is some information on this part of the donation process.

What does the donation operation involve?

The donation operation is conducted with the same care as any other operation, and the body is always treated with respect and dignity. This operation is performed by highly skilled surgeons and health professionals.

Similar to other operations, a surgical incision is made in order to retrieve the organs and this incision will then be closed and covered with a dressing. Depending on which organs and tissues are being donated, the operation can take up to eight hours to complete.

What happens after the operation?

Following the operation, the donated organs will be transported from the operating theatre to the hospitals where transplantation will occur, in Malta or abroad. Certain transplant operations such as the heart, cornea, and kidney transplants are carried out in Malta. Organs that are not to be transplanted in Malta are offered to Transplant Centres abroad, mostly to Italy due to its vicinity to Malta (since time from death to transplantation must be the shortest possible).

If the family would like to see their loved one who has passed away after the operation, this can be arranged. The donation process can take up from 24 to 48 hours, and should the family require any details, they can do so by contacting the Transplant Co-ordinator.

Will the person look different?

When a person has died and blood and oxygen are no longer circulating around the body it is usual for them to appear pale and for their skin to feel cool. The donation operation does not result in any other significant changes to the person’s appearance. The surgical incision made during the operation will be closed and covered as in any other operation.

Will funeral arrangements be affected?

Organ and tissue donation does not affect funeral arrangements. Viewing the loved one and an open casket funeral are both possible. If a coroner’s investigation is required, this may delay funeral arrangements.

When is a coroner’s investigation required?

Some deaths, such as those following an accident or due to unnatural causes (e.g. poisoning, suicide), are required by law to be reported to the court and investigated by a coroner. Any decision about donation does not influence whether a coroner’s investigation is required. The hospital or the Transplant Co-ordinator staff will inform the family if the circumstance of the death requires reporting to the coroner.

Can the family change their minds about their donation decision?

Yes. The family can change their minds about donation at any point up to the time when the person is taken to the operating room.

What are the religious opinions about donation?

Most major religions are supportive of organ and tissue donation.

Will the person’s family be expected to pay for the cost of donation?

No, there is no financial cost to the family for the donation.

Which organs and tissues will be donated?

The Transplant Co-ordinator will discuss with the family which organs and tissues may be possible to donate. This will depend on the person’s age, medical history and the circumstances of their death. The family will be asked to confirm which organs and tissues they agree to be donated. They will be asked to sign an authority form detailing this information.

Does the person’s family have a say in who receives the organs and tissues?

Organ and tissue allocation is determined by transplant teams in accordance with international protocols, medical criteria and according to the hospital organ/tissue allocation policy. The policy is based on medical and ethical criteria, (such as best match and waiting time) to ensure the best possible outcome of the organs/tissues donated.

Will the person’s organs definitely be transplanted?

If the family supports donation, everything possible will be done to make sure those wishes are fulfilled. At the time of the donation it can sometimes become clear that organs intended for donation are not medically suitable for transplantation. The Transplant Co-ordinator will discuss this with the family if it arises.

Is transplantation always successful?

The majority of people who receive a transplant benefit greatly and are able to lead full and active lives as a result. Transplantation, however, is not without risk including that of the transplant surgery and the ongoing treatments required after transplantation.

Will the family receive information about the patients who have benefited from the donation?

Health professionals involved in donation and transplantation must keep the identity of donors and recipients anonymous by law.

Today I witnessed the most incredible things. Today I saw a miracle! I saw the sun rise. I saw a child laugh. I saw a family kissing each other. I saw a flower in my garden. Each one of these was a miracle, because they are the miracle of my life.

And every day for the past seventeen years I’ve enjoyed and appreciated the second chance at life that organ transplantation has provided to me.

On behalf of all transplant recipients I would like to give thanks to all those people who have donated tissues and organs. Through their love of life and decision to help others at the time of their death, they continue to provide life to other human beings.

Let us also acknowledge and give thanks to the families of all donors. People who, in times of trauma unimaginable to most, have the strength and compassion to see beyond the tragedy; who have respected the decisions of their loved ones or made decisions on their behalf; to allow others to live a life and have a quality of life that otherwise would not have been possible.

Every day I give thanks to the two people who loved enough to give me, a total stranger, a heart that beats without missing a beat so I can see a sun rise; I can feel the warmth of a hug; I can smell the fragrance of a flower; I can taste the freshness of a fruit; and I can hear the laughter of a child. These are life’s everyday miracles that most people take for granted. What is ordinary to some is extraordinary to me.

Fiona Coote

What is grief?

The death of someone we love is a universal experience and the feelings of grief that accompany the loss cannot be avoided. It is particularly hard when the death is sudden or unexpected and there is no time to prepare – no time to say goodbye.

You may feel shocked, confused and frightened. The way you see the world suddenly changes. Your sense of safety and security is shaken, and a feeling of being in an ‘unreal world’ takes over. There may also be a feeling of anger and a strong need to blame someone for what has happened.

Many factors will influence the impact of the death upon you. These include the age of, and relationship with, the person who has died as well as the circumstances surrounding their death.

How will grief affect me?

It is important to be aware that there is no specific ‘pattern’ to grief. There are no set time limits within which you should be ‘feeling better’ and no set sequence of ‘stages’. As individuals we will all vary in the way we cope. However, there are some reactions that are commonly experienced by bereaved people. We have listed some of them below that you may recognise in yourself, and also some things that you might like to consider. To experience any of these is completely normal.

Emotional

- Often numbness and a feeling of disbelief help you to cope in the first few days or weeks. Don’t be surprised if things feel worse when that numbness wears off.

- Recognise that anger is a normal part of grief.

- Give yourself permission to grieve – don’t try to be strong for everyone around you.

- Let people know how they can be helpful – with practical tasks as well as providing emotional support.

- You may fluctuate between needing the company of others and wanting some time on your own. Be open with people – make those needs known.

- It may be hard to concentrate for long on even simple tasks – don’t expect too much of yourself.

- You may experience strong emotions during bereavement, which may alarm you. This is not unusual, but if you are worried by the intensity and duration of your feelings, don’t be afraid to seek professional help.

Physical

- It is especially important not to neglect your own health. You are under great stress and will be more vulnerable to infections. You may feel run-down.

- Try to eat reasonably well, even if there is no enjoyment in it.

- Your sleeping patterns are likely to be disturbed. Try to take some time out during the day just to rest when you can.

- Avoid excessive alcohol, drugs or other harmful substances.

- If you have symptoms that are worrying you, seek advice from your local doctor.

Social

- Friends and family are often more supportive early in bereavement but this may lessen as time goes by. It is important to be able to reach out to them for help when you need to. Don’t wait for them to guess your needs. They will often guess incorrectly and too late.

- Social gatherings may elicit feelings of anxiety especially in the first weeks and months. Be gentle with yourself and choose to be with people you trust.

- During a period of grief it can be difficult to judge new relationships. It is hard to see new relationships objectively if you are still actively grieving. No one will be a substitute for your loss. Try to enjoy people as they are.

Financial

- Avoid hasty decisions. Try not to make major life decisions within the first year unless absolutely necessary.

- In general, most people find it best to remain settled in familiar surroundings until they can consider their future more calmly.

- Don’t be afraid to seek advice from someone you trust.

Spiritual

- Personal faith may be a great source of comfort during bereavement.

- Some people experience a dream, or touch, or sense of visitation from the person that has died, and this may be comforting.

- As we grieve, we actively consider and re-evaluate our beliefs and views about the way the world works and our place in the human condition.

- We may struggle with the meaning of our loved one’s death at this time.

- It may be helpful to consider the emotional legacy you have gained from having had the joy of knowing and loving the person that has died.

- Your local priest may be able to provide support.

- Some people report that transitioning from loving the person in presence to loving in absence is extremely helpful.

What may help?

It takes time to adjust to an environment in which the person you love is missing. Things you least expect will trigger memories and may overwhelm you with emotion – a piece of music, an empty chair, the smell of a favourite perfume.

Learn to recognise what works for you. You will quickly identify family members or friends who will allow you to be yourself and express your grief in a way that is meaningful for you. Talk about the person who died and encourage others to share their memories too. Sometimes people are hesitant to talk about the deceased for fear of upsetting you more. They may wait for you to give them permission.

You may find that spending a little time on your own also helps – writing your feelings in a journal, visiting a special place that feels safe and may hold happy memories for you, putting together a memory book. Different things might work for you at different times.

Each family member had his or her own special relationship with the person who died and will feel the impact in a different way.

These feelings will not last forever, though at times it may seem as if they get worse rather than better. Gradually over time you may notice these differences:

- you have more good days rather than bad days.

- you can share memories about the person who died and experience more pleasure than sadness.

- you can actively begin to reinvest in life and plan for the future.

Children and grief

Children’s understanding of death will vary depending upon their age. Even young children will be aware something very bad has happened but may not be able to comprehend the seriousness of it.

Their home and family provide the only sense of security they know. They are likely to be very sensitive to the dismay and disruption among those they usually turn to for comfort. It is important that they feel loved and reassured.

You may notice that children’s behaviour regresses. They may act as they did when they were much younger. For example:

- they may insist on staying close by you and be very fearful of being separated from you.

- their sleep patterns may be disturbed and include bad dreams.

What might help?

There are things you can do to help and with this in mind we have listed some of them below:

- Young children often express themselves through play. Take time to play with them and ask them to explain what they are doing.

- Be open and honest with them – explain what is happening as simply as possible.

- Involve them – they need to be able to ‘do something special’ for the person they loved – make a garden, plant a flower, take something they have made to the cemetery. Be creative.

- Let the school know what has happened as soon as possible. This will give the teachers time to plan how best to support children when they return to the class.

- Just knowing that some of these reactions are common can be reassuring for you as a parent. However, if at any time you are concerned about how your child is coping, do not hesitate to seek professional advice through your local doctor.

How to cope with anniversaries and special days?

Anniversaries and special days will never be quite the same without the person you loved. The first year in particular can be especially painful. There is a sense of ‘building up’ to each important day with an increasing feeling of anxiety as to how you might ‘get through it’.

What might help?

- Plan ahead – talk openly with the family about the day – everyone will have different needs and expectations.

- Children in particular will be seeking reassurance that family life will continue ‘as normally as possible.’

- Share the day with people you enjoy and with whom you feel comfortable.

- You may choose to make a change from the usual family ritual and create a new family tradition.

- Try to make the day meaningful in some way.

- Allow others to help you in the planning, whilst remembering that it is your special time.

- Allow yourself to share both laughter and tears with those around you – it may help them to express their feelings too.

- Be creative in remembering your loved one – light a candle, buy a special decoration for the Christmas tree, buy something special that all the family can enjoy.

- Children may wish to draw a picture or write a letter for the person who has died.

- Be gentle with yourself – set realistic goals.

- Treasure memories of your loved one – you will always carry them in your heart.